PC players have long been used to an “all sales are final” policy on their games. In the US, most shops wouldn’t accept a return after the box had been opened (at least, not without a knock-down, drag-out fight at the customer service desk). In the digital era, refunds have been extremely rare, and most digital stores wouldn’t offer them except in truly unusual circumstances.

But two months ago, practically out-of-the-blue, Valve turned that on its head. You could get refunds on Steam games. The policy change was not universally beloved at first, and several developers were alarmed by the early results and what it heralded for the future of PC game sales. Now that the policy is two months old, however, it’s starting to look a lot better to both developers and publishers.

It’s still early yet, and everyone we spoke with is operating on very limited data. The long-term trends for game returns are still a mystery. But for now, the system seems to be offering more advantages than disadvantages.

“I can say daily sales are up by more than 30%, which is big enough that I don’t imagine refunds are completely negating it,” says Tom Francis, developer of Gunpoint and Heat Signature. “It’s the first time the game’s daily sales rate has ever gone up and stayed up – the usual pattern is a slow decline with brief spikes for discounts.”

Facepunch’s Garry Newman finds that returning the customer’s money solves a lot more problems than it creates.

“It kind of gives us an out, really. And that’s important,” he tells us. “Their hardware might be crap. So the game might not work on their hardware. It might be incompatible some other way. We use the Unity engine, so …if it’s an engine fault, we can’t correct that. Because we don’t have access to it. …So come have a refund.”

That’s not an offhand way to dismiss unhappy customers. Refunds turn what could be a terrible forum flame post or an embittered user review into – hopefully – a no-harm, no foul situation.

That’s certainly one of the things that Paradox are hoping to see from the refund system.

“We had an interesting situation when we released Horse Lords [a Crusader Kings 2 expansion],” says Susana Meza Graham, Paradox’s COO. “It released on schedule, but something happened and it didn’t download for the first hour, so there was a technical glitch and we got slammed with a lot of bad reviews, because people weren’t able to install it. We’re thinking that having a more established refund system… might reduce those kinds of reviews. That are more related to the purchase experience itself than the game itself.”

That might be a little optimistic, given that Horse Lords came out after the refund system was in place, and angry forum trolls will be angry forum trolls. But giving people their money back seems like the simplest solution to your everyday unhappy customer.

Of course, angry customers have always had a chance of getting a refund on Steam. It was just rare and often wildly inconsistent in how it worked.

Paradox issued mass refunds on at least one occasion a few years ago, when a major release was plagued by bugs and broken features. The publisher had to make things up to a lot of their customers with refunds… but that only showed how inadequate Steam was to the task.

“It was actually quite a lengthy process,” she says. “Not because of the volume, but because there was no process in place and it all had to happen manually.”

In essence, Paradox would have to find each customer, order by order, and then give the info to Valve so that Valve could process the refund. It was a huge, labour-intensive undertaking.

And that’s really what the refund policy fixes.

“From our point of view, anytime you have to talk to Valve, it’s kind of failed as a platform, really,” Newman admits. “Because we want to do it ourselves. And I think Valve feel the same way. …They’ve got more support people than game developers. They want an automated system. Like, the end goal for Steam is to get rid of Greenlight and just let people make games as they like. It needs to be self-moderating.”

Meza Graham also hopes that knowing the refund option is there will encourage more players to take a chance on games they might otherwise hesitate before buying, but she’s not sure the two-hour time limit on returns will really allow for that kind of behavior when it comes to Paradox games.

“With [Paradox Development Studio] titles in particular — with them being a little more complex — what we’re hoping to see is that knowing that you can get a refund if it’s just not your cup of tea, will make the barrier to entry lower. That’s certainly what we would hope. On the other hand, I don’t know how much you’d be able to do in two hours in one of our games.”

The two-hour limit is causing a slightly different issue for Facepunch, one that Newman can’t quite solve yet.

“The only problem we’re seeing with the two-hour time limit is that we’re seeing a lot of persistent cheaters who will make a new account and cheat on it for 1.9 hours and then refund. Then they’ll make a new account, cheat for an hour fifty, and refund again,” Newman says

The cheaters are using throwaway Steam accounts, so Facepunch can’t ban them, but they’re working with Valve on a solution while trying to come up with one themselves.

“We were thinking for the first two hours you can only play on certain servers, or something like that,” he continues. “But it gets a bit shady because …you’re saying you can’t really play the game until you’ve played it for two hours, because [by] then you can’t refund. That seems a bit shitty, really.”

Every developer we spoke with is currently working from very limited information about how Steam refunds are performing, but there was broad consensus that the feedback they provide should be better if it’s going to help them make decisions and respond to customers.

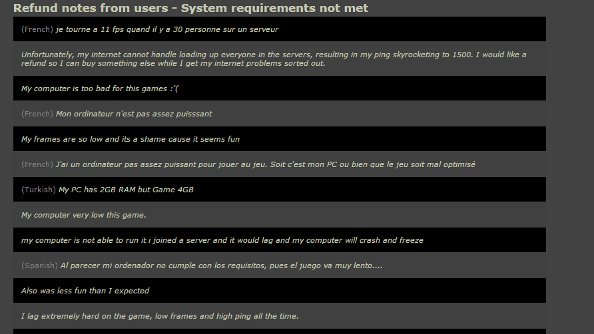

While developers receive a breakdown of the reasons why their games have been returned, it’s very much a raw data dump that’s hard to parse.

“It’d be more useful if [refunds] were shown per week, per month, per day. So then we could say, yeah, people have stopped being put off by framerate issues as much, so we must be doing a good job there. Because people can actually put reasons about why they got the refund, so we can go there and click and see what people actually write,” Newman says.

So far there doesn’t seem to be much of a pattern when it comes to what gets refunded, but it also looks like refunds are not a predictable percentage of total sales. There are clear cases where the refund rate is higher or lower, but the pattern is tough to parse right now.

“As far as I can tell,” writes Cliff Harris, “talking to other devs, the refund rate does vary a lot between games. I do wonder if it’s related to price, with people not bothering to ever refund a $1 game, but being more likely to if it cost them actual proper money, but that’s just a theory.”

Still, developers like Newman and Tom Francis mostly appreciate the fact that there are times when giving a refund is just the right thing to do.

“I don’t really know if it works out to more income or how much, but I’d be delighted with this system even if it was losing me significant money,” says Francis. “It’s great to think all our income is coming from people who are happy they gave it to us.”

Newman is even more pointed.

“I think what it comes down to really is: is the game worth buying, and is it worth keeping after you’ve bought it? It’s that simple to me.”