Being good is Tyranny’s hard mode. Well, that’s not strictly true: Tyranny’s hard mode is ‘Hard mode’. But outside that gruelling combat experience, the way to bruise yourself most badly in Obsidian’s new isometric RPG is simply attempt to be an alright human being.

Related: the best PC RPGs.

Perhaps you think yourself a dab hand at heroics, and at navigating the familiar morality systems of RPGs. But let me tell you – I thought the same. In Tyranny, evil is the status quo, and everything about this strange and bold rewrite of the RPG formula conspires to keep it there.

Let me explain.

Imagine you heard about the Mass Effect series for the first time today. And, against all sensible advice, you began with Mass Effect 3. That’s a little what starting Tyranny feels like – being thrust into a world you don’t know, and having to grapple with a story already in its third act.

By the time you pick up the reins, the vast majority of that world is under the control of Kyros, a vague and malevolent force who has instilled his own cruel brand of order across the realm. And Kyros’ armies are a few years into a war with The Tiersmen – a stubborn pocket of disparate rebel groups.

Although you, the player, are new to the war, your character is not – they adjudicated the disputes of Kyros’ squabbling forces for years prior. To reflect that fact, Tyranny gets you to run through a quick choose-your-own adventure sequence before the game proper picks up. Beautifully animated as a war room map strewn with miniatures, this Conquest Mode determines how you resolved tactical disagreements and prisoner-of-war problems in the early days of the campaign.

It’s almost as if Obsidian have checked for an imported save and, not finding one, asked you to fill in the blanks instead.

As a consequence, playing Tyranny feels like waking up in the middle of an important meeting and having to bluff your way through. You don’t know anyone, but everyone knows you – and moreover, they all have strong opinions about actions you did or didn’t take during the siege of the Bastard City in 428 TR. For example.

It’s a lot to ask a new player to keep in their head – and goodness knows there’s enough reading involved in the first hours of Tyranny already. Thankfully, any brainfarts are handled fairly deftly via lore tooltips, which fill your knowledge gaps mid-conversation without recourse to a codex buried in the menus somewhere.

What you’re still left with, however, is profound imposter syndrome, as you sprint to catch up with a war already coming off the tracks. Any intentions you might have had of improving the lot of the put-upon Tiersmen swiftly melt away – replaced by the need to fake it til you make it as a Judge Dreddian figure of totalitarian justice.

Well: that’s what I’ll tell anyone who wonders how I found myself in the middle of a crowd of soldiers ordering the execution of a bound and unarmed prisoner, anyway.

Overwhelmed, clinging to a position of authority and fearing exposure, you’re constantly subject to the gaze of Kyros’ other minions – the haughty, brutal Disfavored legion; the Mad Max-style war boys and girls of the Scarlet Chorus; the disparate companions who’ve ended up under your command.

One, Verse, shrugs noncommittally at the suggestion she might be a spy for her general in the Chorus. Meanwhile, her Scarlet comrades are only too happy to explain that they’ll jump you, or any other officer, at the first sign of weakness. Try showing even a morsel of mercy in that kind of workplace.

Your immediate colleagues are no kinder.

“Assume you are being watched,” warns Fatebinder Calio. “But don’t concern yourself. That’s no more than any citizen of the Empire can expect.”

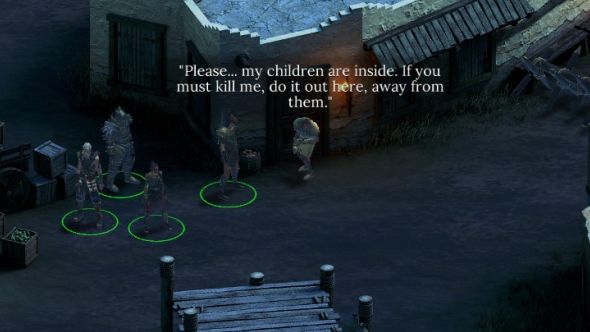

Observed by both higher authorities and the underlings you’re supposed to be managing, it becomes an act of self-sabotage to talk to the Tiersmen rather than slaughter them on sight. And before you know it, you’re doing some pretty horrible stuff. This is the sort of awfulness enforced by bureaucracy, rather than applied willy-nilly by a player who fancied trying Chaotic Evil for a change.

The peer pressure is only compounded by a reputation system which, on first glance, seems backwards. These are binary morality thermometers like those employed by Knights of the Old Republic and Fable in the ‘00s. In those games, they encouraged you to game the system: why engage with the complicated quandaries of the scenario in front of you, when it’s pretty clear which option is going to award you some light-side points and push you further towards those late-game Jedi abilities?

RPGs got more savvy – pushing the numbers beneath the surface and leaving you to worry about your standing with factions and companions. But Tyranny reverts. Here’s a bar that measures your relationship with the Disfavored – their approval and their growing anger. Here’s another that tracks how much Verse likes you, and how much she fears you.

So you start to play the systems – picking outcomes not because they’re the right thing to do, but because they’ll impress some powerful weirdo bathed in green flames named The Voices of Nerat. They become tactical decisions: put all of your eggs in the Disfavored basket, and you can count on them to stick by you if things ever kick off with the Chorus.

Soon enough, you’re a bad person – blind to the impact of your decisions beyond the insular political consequences within Kyros’ organisation.

I know what you’re thinking. Excuses, excuses. You’ll do better – fight harder for the people caught underfoot by the overlord’s war machine. Just think of me when you’ve traded that idea for one more day in power, free from insurrection or accusations from your superiors.

I mean, think about it: fear is just another way of maintaining order, and order keeps everybody safe. Isn’t that a kind of good? Sort of?