Watch Dogs is the culmination of five years of development and an even greater number of years of open world iteration. It’s empowering, fast and filled to the brim with explosive action sequences and cinematic car chases. I did not expect, half way through the game, to keep making excuses to stop playing. A quick cigarette on the balcony became a cigarette and a glass of whisky. Patting the dog became leaving the house and taking the dog for a walk.

It’s not that Watch Dogs doesn’t have plenty of tricks to keep my attention, though. There’s a lot to do in Chicago. A lot of driving down streets. A lot of shooting men from behind cover. A lot of disconnected mini-games, side missions and optional content. Yes, a lot of things that have been done many, many times before. Some of that, though, is extremely good fun.

Aiden Pearce is an odd fellow. Cursed with a Christian-Bale-as-Batman speech impediment, he talks to himself in hushed tones spouting vaguely pulpy noir nonsense. He’s angry, in that stone cold, occasionally simmering when pushed, way. He messed with the wrong people and got his niece killed. He’s wracked with guilt, because it’s entirely his fault, so now he’s taking it out on some bad men. Responsibility only goes so far with Mr. Pearce.

He’s a lot like Assassin’s Creed’s Connor: brooding; not too sharp; terribly, terribly dull. And he’s entirely inconsistent. One moment he’s saying that he doesn’t want to kill, and the next he’s blowing up people and demolishing the city’s infrastructure. All this absent in-game consequences, of course. But who he is – an angry, stupid uncle – is not nearly as important as what he does. And what he does can be immensely entertaining.

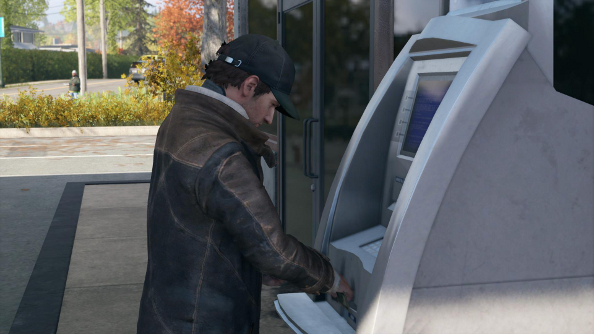

Aiden is a Fixer, a criminal with a diverse set of skills from high speed driving to gunning down armies of vaguely bad men. But what sets him apart from his fellow Fixers is a seemingly magical phone that can effortlessly hack into Chicago’s ctOS grid, allowing Aiden to manipulate traffic lights, phones, cameras and even explosives.

And that magic phone shines more brightly than almost any other aspect of Watch Dogs. It takes the increasingly rote – in the context of video games, at least – activities of driving very fast and getting through buildings filled with brain dead guards and throws in a twist that elevates these activities far beyond what they would be without it.

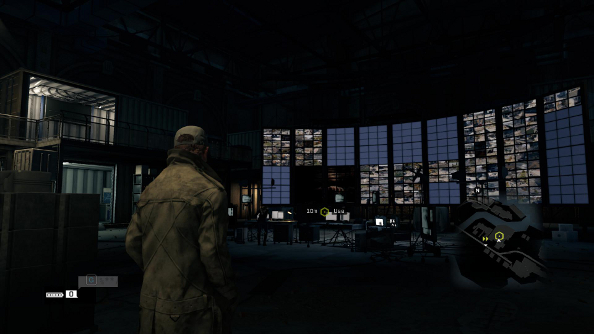

With phone in hand, Aiden can shut down gang bases and heavily guarded corporate headquarters without breaking a sweat. Sometimes he doesn’t even need to go inside them. The rule is: if Aiden can see a device that can be hacked, he can hack it. Thus, hacking becomes a game of navigating the environment through cameras, looking for and then exploiting vulnerable systems.

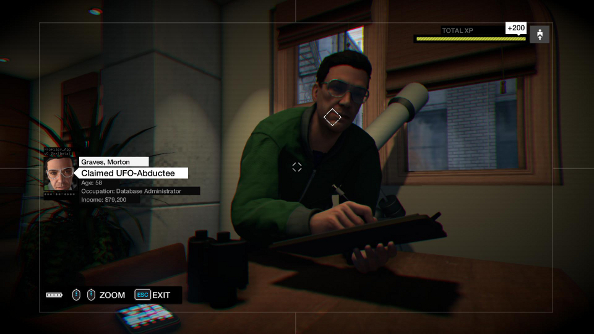

There’s some light puzzle solving involved. Using cameras, both stationary or attached to phones, Aiden can do a bit of recon, memorise guard patterns, look for ways to take out enemies without having to even be near them – an exploding transformer here, a crate dropped from a crane there – and then hunt down the objective.

In the midst of a car chase, he can manipulate traffic lights, raise bollards, close gates and even blow out gas pipes underneath the street, all in an effort to halt pursuers. Similarly, these powers are endlessly handy when chasing enemies or setting up ambushes.

It’s empowering and sometimes quite clever. When it’s all fresh and new, experimenting with the most efficient ways to take out whole bands of foes with just a few hacks is a compelling affair, making one feel like a devious super-powered villain. There’s a singular joy to taking out three gun-toting menaces with one hacked grenade.

But as one of the few things that makes Watch Dogs stand out from the plethora of other open world games – many of them made by Watch Dogs developer Ubisoft Montreal – there’s a lot of weight on the shoulders of this single system. And sometimes, it’s just not strong enough to carry the whole game.

It’s when Aiden is behind the wheel of a car or riding a motorcycle that hacking starts to feel repetitive. While infiltration missions give Aiden myriad paths and powers, various permutations of three core skills – spying, distracting and killing – when driving, he’s a lot more limited. They are still extremely helpful abilities, but they all do the same thing: total cars. Raising bollards causes a car crash. Manipulating traffic lights causes a car crash. Blowing up gas pipes causes a car crash.

But undoubtedly the worst implementation of hacking in Watch Dogs appears in the form of a horrifically uninspired mini-game. There are many, many forgettable mini-games in Chicago. You can play chess or poker, for example, though who knows why anyone would want to when there are high speed chases just around the corner or companies to topple just up the street. The hacking mini-game is the weakest of the lot.

There’s a simple network of white lines, and Aiden has to make some of them blue so he can break through the system’s defenses. This is achieved by spinning a few junctions in the network. It’s a wee bit like BioShock’s hacking mini-game, but actually less involved. There’s no excuse for such a slipshod hacking mini-game in a title that’s all about hacking.

Yet Aiden’s ability to manipulate both the environment and people remains one of the strongest aspects of Watch Dogs. It doesn’t carry the whole game, but it’s a treat after putting up with considerably drearier elements that have been shoehorned in simply because it’s an open world affair.

This is Watch Dogs most glaring problem: it tries to be the ultimate open world game. There’s not much focus. This can lead to the occasional success, like the mimicry of Far Cry 3 and Assassin’s Creed’s climbing of towers to spot more things on the map. The core of that system has been retained, but given an appropriately Watch Dogs flavour, with Aiden physically navigating the environment and also using cameras to hack his way into a ctOS outpost.

But far more often, the attempts to squeeze in every open world mainstay lead to extremely mixed results. There are the broad features, of course, like driving and combat. The range of vehicles is poor, not because there aren’t many of them, but because – despite a variety of stats – they all tend to handle like tractors. Driving is something you have to do to get from A to B, but it’s never a pleasurable experience.

Combat comes laden with its fair share of problems. Enemies are stupid drones, and no combat scenario is any real challenge once one purchases a grenade launcher, which is available very early on. It’s very poorly balanced. Worst of all, Watch Dogs features the criminal addition of baddies with loads of armour. That’s how Ubisoft decided to up the challenge. They look like Space Marines, sticking out like a sore thumb compared to the fairly down to Earth speculative fiction setting, and are just as dumb as their more vulnerable cohorts.

But if you can overlook the armoured fellows and not immediately purchase a grenade launcher, there’s the occasional moment of nuance – at least compared to the shooting in other open world games. Enemies, though lacking intelligence, are still capable of using and sticking to cover, and given enough time they will flank Aiden and try to flush him out with explosives. The use of explosives also makes for some of the more entertaining moments in combat, where Aiden hacks said explosive before it can be used against him, sending his foe into a panic and, with a spot of luck, blowing him to smithereens.

Stealth rears its head, and again it’s a mixed bag. It’s tonally appropriate, though, since Aiden pretends he doesn’t like killing (which is complete bullshit) and would rather use guile. At the recon stage, using cameras to spot enemies and memorise patrol routes, it’s pretty solid, but from then on it’s just a matter of using cover and occasionally employing a blackout hack that shrouds the city in darkness.

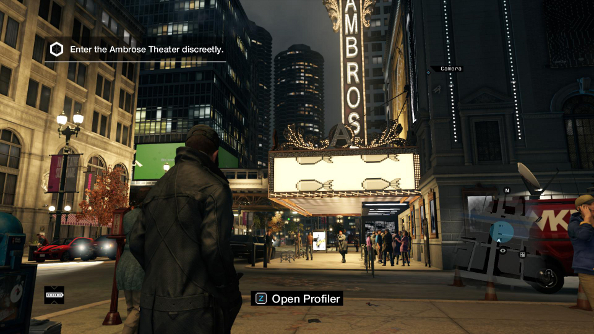

The blackouts should have been impressive. Visually, they certainly are. But the only purpose they serve is to allow Aiden to sneak around. He blacks out an entire city just so he can’t be seen in one tiny part of it. Driving around the temporarily dark city, looking up at the eerie, lonely skyscrapers almost makes it worth it. But it lacks the sort of impact you’d expect from a city-wide mini-disaster.

When Aiden isn’t busy with the tiresome campaign to get revenge and also save his sister – women in Watch Dogs exist to be sexy or be rescued – he’s faced with a mountain of diversions. Poker, chess and “drinking” are the most pointless inclusions, and not worth any time at all. Then there are digital trips, hallucinogenic games, which Aiden can get from dealers around the city. Few are worth more than a look. They sound awesome, but in reality they are repetitive score-based activities.

There’s one where Aiden can control an agile spider tank and trash the city, though, and it’s actually an absolute blast. It can leap onto the side of buildings, throw itself across the skyline, launch a barrage of rockets, or simply step on the Chicago police attempting to halt its merciless rampage. It’s the only digital trip that provides genuine entertainment, but it provides a lot of it.

The Fixer side missions are meat of the side content. They are simple missions that task Aiden with getting into high speed chases to distract the police, shutting down gang strongholds or ambushing criminal convoys. Essentially, it’s the same thing Aiden has to do during campaign missions, but they are shorter and absent the mostly dull cast of hackers and criminals he normally associates with. The focus, then, is on experimenting with his hacking abilities and learning the shortcuts that pepper the sprawling urban environment.

The city itself is a diversion too. On the surface, it’s impressively realised. It’s gorgeous to look at, especially during a storm or during dusk and dawn, and absolutely massive. But it’s a surprisingly shoddy simulation. Wandering NPCs exist merely to be hacked, their money drained from their accounts, or rescued when a criminal is hassling them. Ubisoft has tried to make them seem alive by letting Aiden listen in on their phone calls or read their texts, but the illusion is quickly broken.

Park a car near an NPC, and watch and they flip their lid and run and shriek. They are timid little things. They are pretty inconsistent, though. Completely by accident, I blew up a transformer next to a couple making out in an alley. The resulting explosion killed the woman and blacked out the city. The man’s reaction: to scream, and then slowly turn around and walk away as if nothing happened.

The greatest instance of the simulation breaking down occurred when, not long after I first started playing, I decided to tail a fire engine. I hadn’t seen a single fire in the game that I had not been responsible for, so I wanted to see if random events like burning buildings or car accidents happened when I wasn’t there.

Following the fire engine, I started to notice the same landmarks. We were going around and around in a circle. But then the fireman at the wheel decided to go completely mad, smash through a fence, speed through a park, and then run over about four NPCs before crashing into a wall. The next few minutes saw the fire engine impotently attempt to reverse, then stop, move forward, crash again and then repeat. It ran over another pedestrian this way. Then a call went out on the radio announcing that the fire, which I never saw, had been put out. Good job!

The sense of “been there, done that” pervades Watch Dogs, and it can sometimes feel like work to find the enjoyment in near future Chicago. Until other players break through the walls between universes, that is.

Watch Dogs’ multiplayer is a surprising delight. There are races, which despite the poor handling of vehicles are rocket-fast adventures thanks to the shoe being on the other foot, becoming a victim of another hacker’s manipulation; cooperative shenanigans; and most importantly, invasions.

When a player invades a game the encounter plays out like Dark Souls’ phantom invasions and the hide and seek multiplayer of Assassin’s Creed. There’s tailing and hacking, with the primary goal of not being detected. Players are alerted to invasions and given a general area to search, but the rest is up to them, using the phone to profile individuals until they find the enemy hackers.

Such instances are filled with tension as the invader gets closer and closer to stealing data, and it can drive one to do silly things. I ended up unloading my assault rifle at crowds of people as time ran out, not expecting it to work, but hoping to get lucky. I didn’t hit the enemy hacker, but I did spook them enough so that they stopped hiding in their car and drove off, prompting a chase and, ultimately, a very nasty car crash.

The multiplayer mode’s focus on hacking and the emergent moments that can come out of that system, playing to Watch Dogs’ strengths in a way that the rest of the game struggles to consistently do. That’s what kept me coming back after walking the dog or polishing off a dram.

Watch Dogs is a monster, in size and ambition. But it’s Frankenstein’s monster, with bits and pieces from other Ubisoft properties – Assassin’s Creed, Far Cry, Splinter Cell – stitched together with elements of the open-world Godfather, Grand Theft Auto. Beneath the huge playground, with its dramatic action sequences set across multiple city blocks and plethora of side content, is a game that’s emblematic of the the open world genre’s failings as well as its strengths.

It is Open World: The Game, and as such, struggles to find an identity of its own beyond its entertaining hacking hook and the inspired multiplayer. But those two elements make up a sizeable portion of the game. There are moments of genuine brilliance buried in the game that elevates it above mediocrity, but its reliance on increasingly tired design does it a disservice.

Take a look at our Port Inspection for an analysis of the range of graphics options and optimisation.