It’s seems like it’s impossible to have avoided hearing about them, and if you have then I envy you. NFTs are “an important part of the future of our industry” according to EA. For Ubisoft CEO Yves Guillemot, blockchain is a “revolution” in gaming. Non-fungible tokens, a blockchain-backed means of owning digital assets like ugly drawings of monkeys, are being talked up as the next big thing in gaming, but there’s one problem: no one’s been able to tell me what the Hell for?

For all the interest NFTs are currently generating on social media and in tech board rooms, it’s hard to see a bright future for them in videogames. Most of what they promise for players is already possible using non-blockchain technology, and the one advantage they offer – that of portable digital ownership – is unimaginable in the current universe of triple-A games publishing.

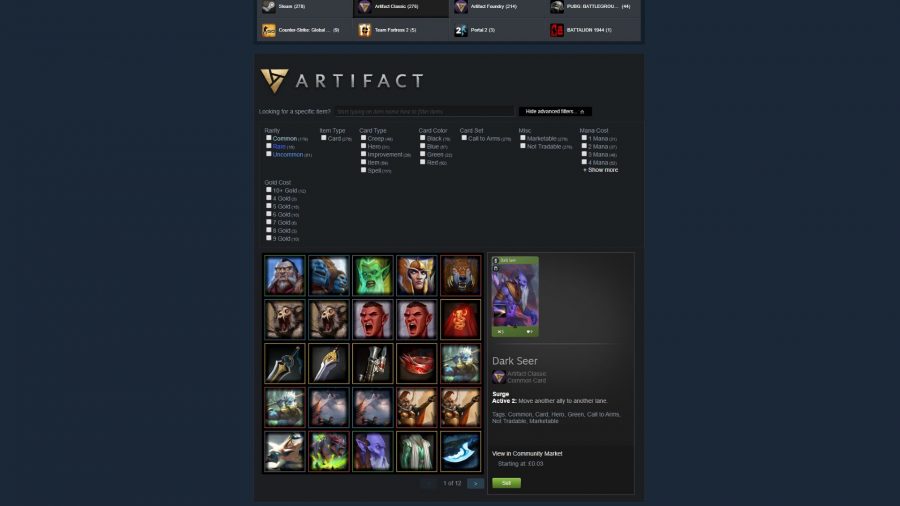

If you want to see the future of NFTs in games, look no further than the fate of Valve’s tragic collectible card game, Artifact. Based on characters and concepts from the massively popular Dota 2, Artifact was designed with help from Magic: The Gathering creator Richard Garfield and used a unique business model: players could buy and sell cards outside of the game by using the Steam Marketplace. Rare and powerful cards would increase in value, but players were free to trade or sell cards as they saw fit.

The idea behind Artifact’s original monetisation model was identical to what the NFT evangelists are promising now: in-game items that don’t depend on the game for their existence, and which can retain and grow in value as ownable assets. Garfield has said that the Artifact team wanted to avoid “manipulating people” with a transparent business model that players wouldn’t have to guess at.

The main problem with this idea is that players hated it. Many balked at the $20 base price for Artifact. Others found that it wasn’t satisfying to play without the promise of free rewards showing up from time to time. This was crucial to Artifact’s design, however: the notion that cards could have and hold value was incompatible with a system that just doles them out to everyone for completing certain challenges or spending a set amount of time playing.

There are two potential outcomes. Either players pay into the system for the game assets (or NFTs, in some hypothetical future game), or the game freely gives them away using some play-to-earn system, as some NFT promoters have suggested. Artifact took the former course, and never wound up with enough players to sustain its ecosystem. Just three months after it launched, the value of a complete deck dropped from more than $300 to less than $100, and now there isn’t a single card on the market worth more than three cents, which is the absolute minimum price for an item on the Steam Marketplace.

Our hypothetical NFT-based card game might instead allow players to earn cards through play, but as noted above, you get the same result in terms of market value. There’s no way for the cards to truly appreciate in value if more copies are constantly being minted.

Even if some NFT-based game solves this problem one day, it still won’t have made a compelling case for its existence. Though Artifact was a failure, it demonstrated that all of this is already possible without using blockchain technology. Games can use conventional database systems like the Steam Community Marketplace to do everything you’re realistically going to see offered by games touting NFT integration, and these don’t have the astronomical energy costs required by blockchain technology.

The best-case scenario for NFTs in games, then, is that they duplicate existing systems in a far less efficient way. However, NFTs have one more big trick up their sleeve. Their staunchest advocates will always be quick to remind you that blockchain allows for decentralised ownership – by using this tech, you’re no longer simply using an account on someone else’s servers, you really own the assets yourself and can do whatever you want with them – even take them to another game and use them there.

Maybe there’s a universe in which this is a workable idea in the triple-A games space, but it sure ain’t this one. No major games publisher is going to willingly sign onto a scheme that encourages players to spend time exploring other publishers’ walled gardens of content, no matter how many times the word ‘metaverse’ is used in promotional copy.

‘Engaged hours’ is a metric big publishers use to measure their games’ performance: the more time users spend playing their games, the more likely it is that they’ll spend money on ‘player recurring investment,’ which for Ubisoft represents nearly half of its total digital revenues. The idea that players are going to become true ‘stakeholders’, who are free to take their assets into other ecosystems, is a non-starter. And that’s without considering the technical hurdles that would need to be overcome to make one game’s assets usable in another, which are currently monumental. Where’s the incentive for studios to put in all that work just to give players a reason to take their toys into someone else’s game?

Perhaps some key innovation is on the horizon for NFTs that will change this outlook. It’s possible; the thing about real innovation is that it’s hard to see coming. But as things stand, and I suspect for a long time to come, NFTs are nothing more than a potentially dangerous and costly fad, and Artifact is their first failed prototype.