One of the main reasons I’ve been able to write about games for a living has been the enthusiastic support and understanding of my partner, Theresa. This is a strange career path, but she’s always encouraging me to keep at it – she even listens patiently while I go on about some idea I’ve come up with about wargame design innovation in Unity of Command 2 or a mission I thought was interesting in The Division 2.

Her support has been unfailing over the year we’ve lived together, despite the fact that she doesn’t share my interest in videogames. That’s not quite right, really – it’s not that she’s disinterested or bored by games, but rather, she’s found that almost all games almost instantly trigger severe migraines.

Watching three-dimensional movement on a screen is sickening for her, which makes most games I play impossible for her to join in on or even watch. First-person shooters are all out, of course, but even character action games like Assassin’s Creed Origins have triggered this effect for her. It’s been a source of some melancholy for me that I haven’t been able to share the games I spend much of my time thinking and writing about with the most important person in my life.

Earlier this year, then, I was excited to stumble across a little game called Exorcise the Demons. The idea behind it is similar to that of Keep Talking And Nobody Explodes: One player looks at the screen and interacts with the game itself, while another player finds instructions in a set of printed instructions.

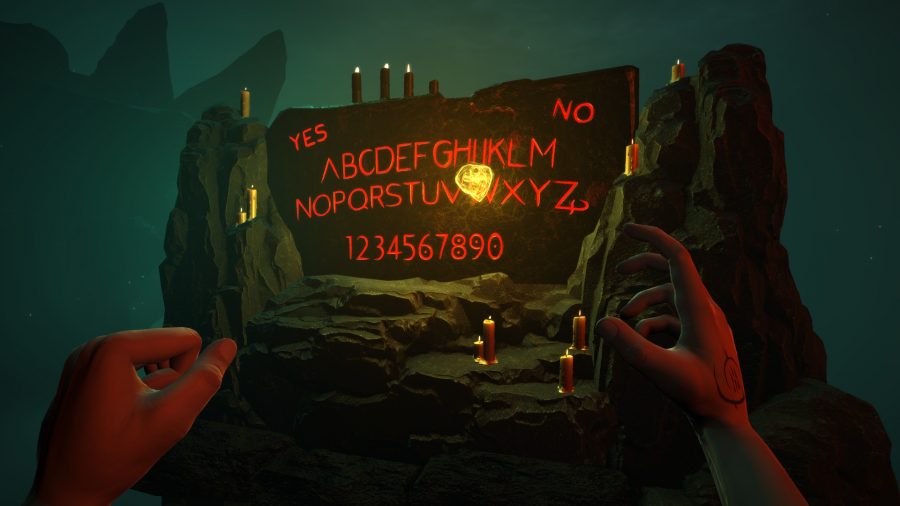

Exorcise the Demons trades the bomb defusal conceit for Army of Darkness-esque banishment rituals, which use floating crystals, circles of power, and ouija boards in order to defeat some evil entity in a surreal hellscape.

This had two big things going for it, as far as I was concerned. First, there are demons. Exorcise the Demons almost looks like it was designed based on the fears of the most feverish “Satanic panic” dreams of parents in the 1980s – a spooky fog fills all the space in the game, ritual candles cluster over rocks, gothic arches and skulls are used liberally in all aspects of the in-game decor. Being as this is exactly the kind of thing I was not allowed to have when I was a kid, it works like catnip for me as an adult.

Secondly, and more importantly, this is a game I could potentially play with Theresa. She’s a voracious reader and, in her professional life, an empathetic leader. I felt this was a rare opportunity to close the gap, and to my delight, she agreed. Unperturbed by Exorcise the Demons’ campy looks and arch premise, she readily took on the role of guide as we fired up the game for the first time.

There were, admittedly, a few hurdles to overcome initially. Despite its charming Necronomicon-inspired aesthetics, it’s not a lovely game to look at, nor is it easy on the ears. The game’s 25 ‘missions’ are held together by a story about a man trapped in an alternate dimension (that’s my character), who’s guided by the voice of a woman who can help him escape (Theresa’s role). Their lines are delivered earnestly, but not well, by two voice actors who are clearly reading a script translated into a haphazard version of English that prevents them from ever sounding like they’re actually talking with each other.

This is made all the worse by repetition, which unfortunately is a factor because these voiceover sequences are replayed every time you begin a level – and because of how Exorcise the Demons is structured, you can end up doing that a lot.

The thing is, we didn’t wind up caring very much. In each level, I would find myself waking up on some floating archipelago of rocks suspended in the air in this hell dimension, and I’d approach the centre, where a gazebo that looked like it was designed in Ronnie James Dio’s basement marked the time we had remaining with a circling formation of pentagrams.

My job was to run to the nearby ritual sites, inform Theresa what I was looking at, and then receive and execute her instructions on what to do, which she’d find in her printed-out version of the Book of Rituals, which comes as a handy PDF in the game files.

“Ok, I’m at the ouija board,” I’d tell her as she sat at the desk next to mine in our home office. She would then flip to the appropriate sheet to work out how to decode the name of whatever fiend it was we were up against. Another ritual had us drawing a pattern in a floating circle of eight stones that changed depending on a set of runes visible on an altar.

The goal of the game is to finish each ritual and banish the local demon before all the pentagrams disappear from around the central structure. There’s a showdown with the beast at the end of each level, and if you’ve performed each rite without making mistakes, you’ll zorch it with a fireball – but if you’ve slipped up even once, you’re toast.

After years of playing games, I’m pretty accustomed to the ‘fail, try again’ rhythm that they get you into, but I worried that our repeated failures during an early level would put Theresa off. But she was rapt from the beginning. Even reading off the page at the adjacent desk, she felt compelled to try again every time we failed – and she celebrated, fists in the air, right alongside me when we finally succeeded.

Exorcise the Demons is not one of this year’s best games, but it is the one game that allowed my partner to share some of the joy that you, dear reader, and I derive from this lovely hobby of ours. It also got me thinking about where games really take place and why.

Extended reality developer and XEODesign CEO Nicole Lazzaro adapted the term fiero – the Italian word for pride – to mean that sense of accomplishment we get from defeating a particularly difficult boss or completing a challenging sequence in games – it’s that thrust-your-fist-in-the-air rush of excitement and triumph that happens the moment we see the words “YOU DEFEATED” on the screen in Dark Souls. Theresa was able to experience fiero while playing Exorcise the Demons, and she got it without ever having to look at the screen or touch the controls.

She was, however, certainly playing the game as much as I was. That led to the realisation that in many games – and for me, it’s strategy games in particular – a lot of the time I spend ‘playing’ them is away from my PC. I’m actively engaged in Total War: Thrones of Britannia while I’m lying in bed thinking about the next step to take in my invasion of Wales.

The time I’ve spent talking on Discord with fireteam members about the next phase of a Destiny 2 raid, or reading Monster Hunter: World wikis for the details about weapon upgrade paths, or researching the minute-by-minute accounts of the Battle of Gettysburg to help inform my latest attempt at Ultimate General – all of that is time invested in those games, during which my mind has been totally devoted to solving problems or overcoming challenges presented by some or another game. It’s a whole undiscovered space available for games to operate within, one that isn’t dictated by graphics processing bottlenecks or available virtual memory.

Granted, this is not a groundbreaking revelation to anyone who’s ever played Dungeons and Dragons or a text-based adventure game. But Exorcise the Demons – rough production values notwithstanding – expands this mental space games inhabit and uses that as its ‘shared screen’, its locus for multiplayer cooperative play.

We’re pushing at diminishing returns when it comes to graphical fidelity in games now: how many more flowing mutant hairs or bouncing sunbeams do I really need to be able to see in Metro: Exodus, after all? Instead, I’m excited to see games push at the boundaries of the cognitive space we’ve reserved for them, and making them into shared imaginative experiences seems like a bright new frontier to explore in 2020 and beyond.