It’s a familiar story for Iron Realms Entertainment founder Matt Mihaly, but not one that has percolated into industry legend: as a young MUD (multi-user dungeon) developer he launches his first game, Achaea: Dreams of Divine Lands. He lives in the San Francisco area, where he’s the leader of his small enterprise, run by a handful of people, and he needs revenue. He knows this as a former stockbroker, someone who once called people and tried to convince them to let him manage their money. He hated doing that, however much sense it made for a bright Cornell grad – albeit one who had spent hundreds of hours playing old text MUDs in the university’s cutting-edge computer labs during the early ‘90s.

Mihaly defies easy categorisation. In some ways, he’s commercially minded and anti-hardcore. But he’s also made a handful of massively complex, text-based RPGs that feature player-run governments, novelistic combat systems, and hundreds of pronoun-adaptable emotes.

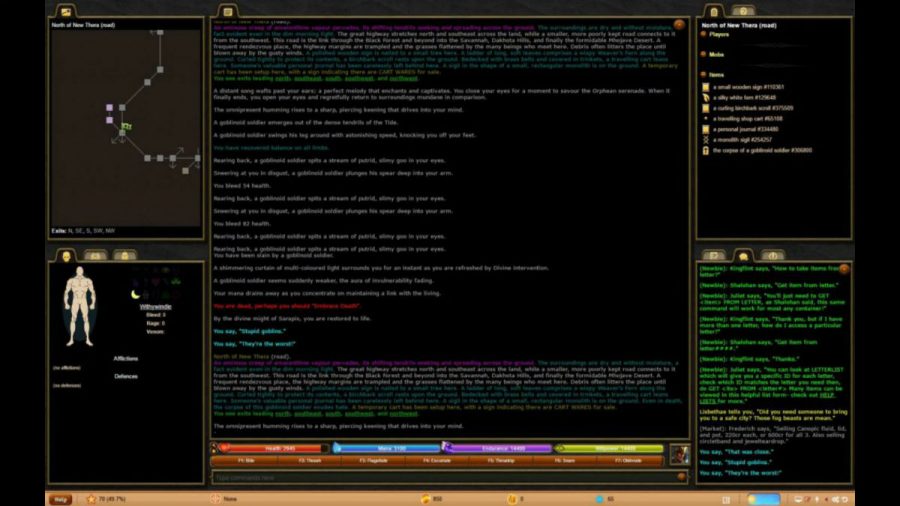

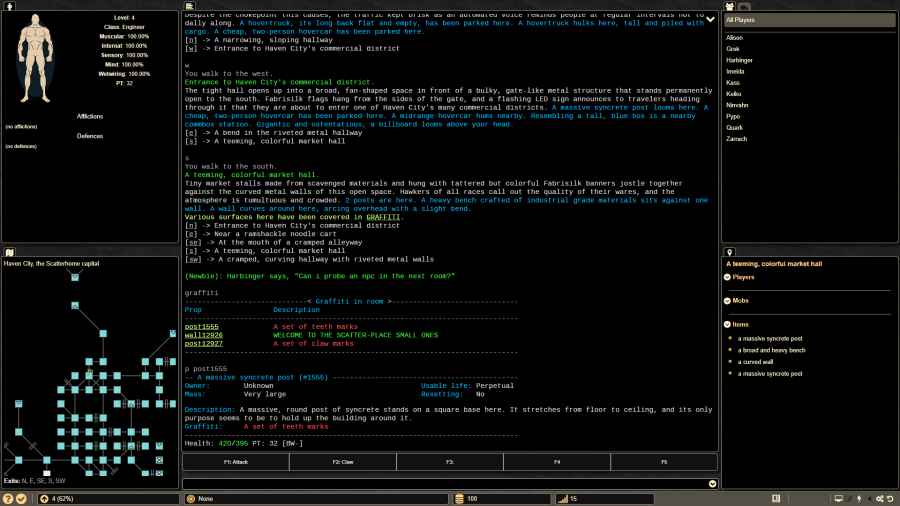

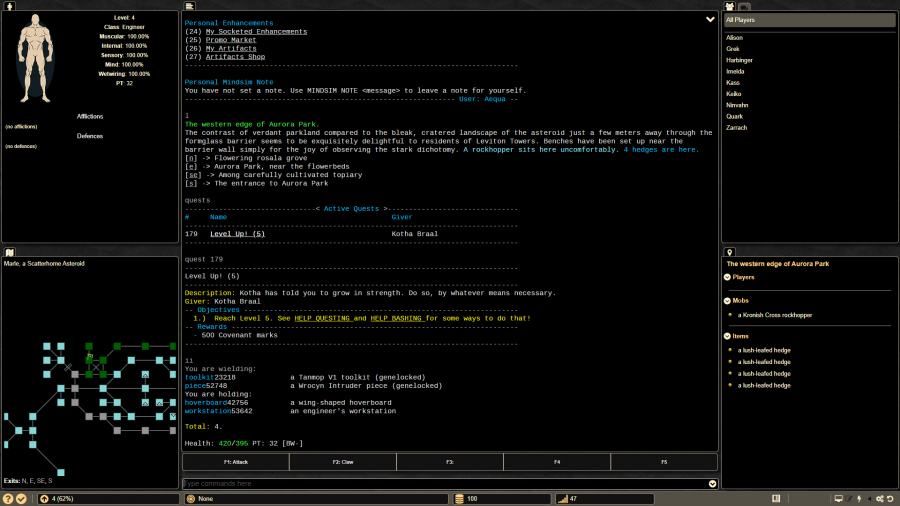

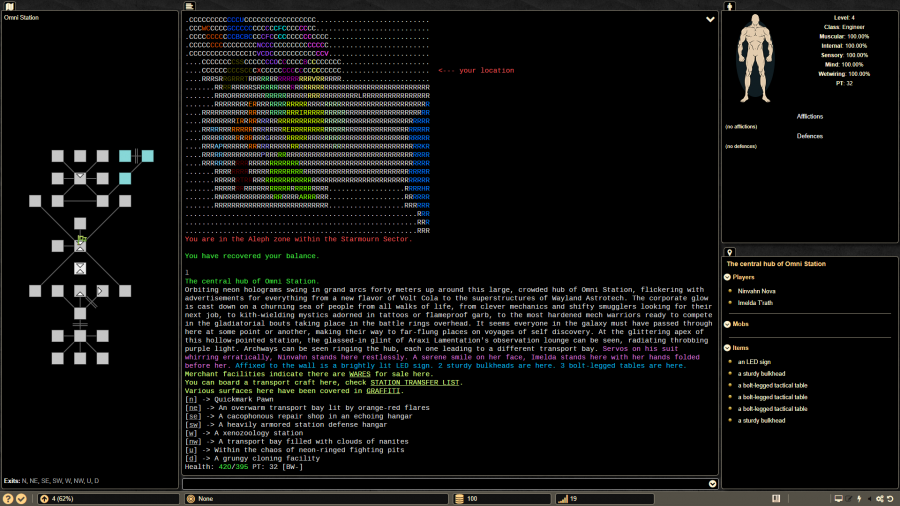

There’s nothing non-hardcore about Achaea or Iron Realms’ science-fiction MUD, Starmourn, which is full of dizzying complexity: 12 player races, a whole galaxy of interconnected rooms, quests, and space stuff, wherein graffiti is a major pastime. So is spaceship construction, leaning against spaceship consoles, and RPG rock bands. In the upside-down world of MUD development, very little stands between those ‘wouldn’t it be cool?’ moments and their subsequent implementation.

Back in 1997, however, the MUD business had turned sour thanks to AOL’s new flat-fee model. Customers no longer accepted the per-hour fees Mihaly had once paid to access online worlds, with flat-fee subscriptions now becoming the standard. And it didn’t help then that Achaea was, according to Mihaly, “partially a buggy mess”. Pushed to improvise, the young founder came up with an early take on the now ubiquitous free-to-play model selling ‘credits’ that could be spent in-game to improve skills. Over time, players asked to buy special items and weapons – something to make them stand out.

Gift horse: Here are the best free MMOs to play today

Mihaly programmed in a small batch of goodies and auctioned them live in the game, generating about $5,000 and a spike in the threadbare game’s revenue. He was floored. Similar transactions had happened before, he suspected, under the table, between MUD admins and players. But now it was all happening above board, and Achaea was getting the money it needed.

He called the special items ‘virtual goods’, but a microtransaction revolution would take several years. Asian MMOs and the Oblivion horse armour controversy launched the idea industry-wide in the ‘00s, and Achaea incorporated what is now seen as a dual-currency model into each new MUD. Players purchase credits with real money and use them to buy in-game currency on a special exchange. While the company doesn’t release revenue numbers anymore, it used to cite more than $15/month per user, and in one case, $75/month.

Some players have argued the games are pay-to-win because the virtual goods include items of power, not just cosmetic flair, which is rather more difficult to monetise in a text game. “I’ve been hearing that ever since I launched Achaea,” Mihaly says. In response, he describes a complex calculus in which people with disposable income, but little gaming time, trade with people in the opposite situation. For example, a player buys credits from the company, gold on the exchange, and a breastplate from a hardworking artisan, stimulating the local economy. On the surface, it’s a win-win-win, but it still doesn’t quite account for the hours put in by the smith or what happens during PVP. The possible objections are endless.

“We try to be good at not giving someone a win button,” Mihaly explains, knowing he won’t convince everyone. He adds that some players “are just not our audience.” Those purists play one of the hundreds of surviving free, hobbyist MUDs that either thrive or persist online in a state of limbo.

Iron Realms’ games tend to favour PVP, which reflects Mihaly’s history. In the mid-’90s, he spent about a year post-stockbroker playing Avalon eight hours a day, eventually becoming its God of Pain. “I really liked that rough and tumble environment,” he tells us, and when an “automation revolution” swept through Achaea in 2001, instigated by a player named Tranquility, he first resisted. Tranquility had written complex scripts to read what the client was shooting out and respond during combat. His work, and that of other coders, had a profound effect as the Iron Realms client now supports scripting. Players are able to trade and sell scripts, making elite PVP a skilled dance that happens too quickly for the human brain.

Most gladiators use macros of some type to automate commands, and many use a MUD client such as Mudlet to filter out the more flowery aspects of combat text – when someone swings a halberd at you, the image of the sun glinting off it is best appreciated after the fact. The more complex, and allowed, scripting automates certain aspects of the game, such as targeting all monsters in a room, selecting attacks, and tracking your own debuffs.

In the late-’90s, Achaea became an object of fascination among game designers. Raph Koster, lead designer of Ultima Online, was a fan. The feature-rich MUD seemed like a promised land of sorts, paradoxically, as graphical MMOs were coming into their own. But on the former MUD-Dev mailing list, of which Koster was also a member, young Mihaly played the role of a Valley capitalist and not a cool guy designer. “I didn’t start Achaea to break new ground,” he wrote in 1999. “Any new ground that is broken is done not for the purpose of breaking new ground, but, in the end, to make money.”

He explained elsewhere: “I raised all the money for Achaea myself, mainly from internet acquaintances that I’ve never met. I had no clue what I was doing when I started out, and [I] still feel like I am just playing business half the time … We’ve had to make sure we’re in the black since day one, and, due to some generous people who had faith in me, that was possible.”

In 2006, Mihaly started a new company, Sparkplay Media, that sought to develop new 3D browser-based MMOs to rival Runescape. However, the first of these, Earth Eternal, ran into revenue problems after going all-in on microtransactions. Sparkplay auctioned the game off in 2010, and it currently lives on a private server.

Iron Realms, meanwhile, has only ever shut down one of its games, Midkemia Online, and it handed another over to community members. Along the way, Mihaly “tried almost everything you can think of”. This includes an active mentorship program where mentors receive a percentage of their students’ purchases, to incentivise helping out newbies.

It sounds well-intentioned on the surface, but one Reddit user called the program “damned near multi-level marketing,” while another said it “left a bad taste in my mouth” when a mentor asked them to pool credit purchases into larger percentages.

Macro transactions: PCGamesN’s best long reads

These days, Mihaly looks on his virtual goods almost as a troubled child. He’s critical, for one, of mobile games and others that exploit what he describes as “compulsion loops”. And even he doesn’t like the games such as Battlefront 2 that ship with half the content locked behind a paywall. Some studios are starting to take a similar view, too – Riot, for example, has chosen not to allow players to pay for card packs with real money. Many countries are now seeking to regulate loot boxes, too.

In the early days of Achaea, the company deployed microtransactions slowly and carefully, like a MUD player charting a new region for traps. Today, entire armies have marched over the same ground, and they keep coming. In the end, how does Mihaly feel about this legacy? He laughs: “There are definitely challenges with the public perception of this.”