Our Verdict

An utterly charming yarn about friendship and kindness that breathes gritty modern life into the quaint JRPG format of classic Dragon Quest.

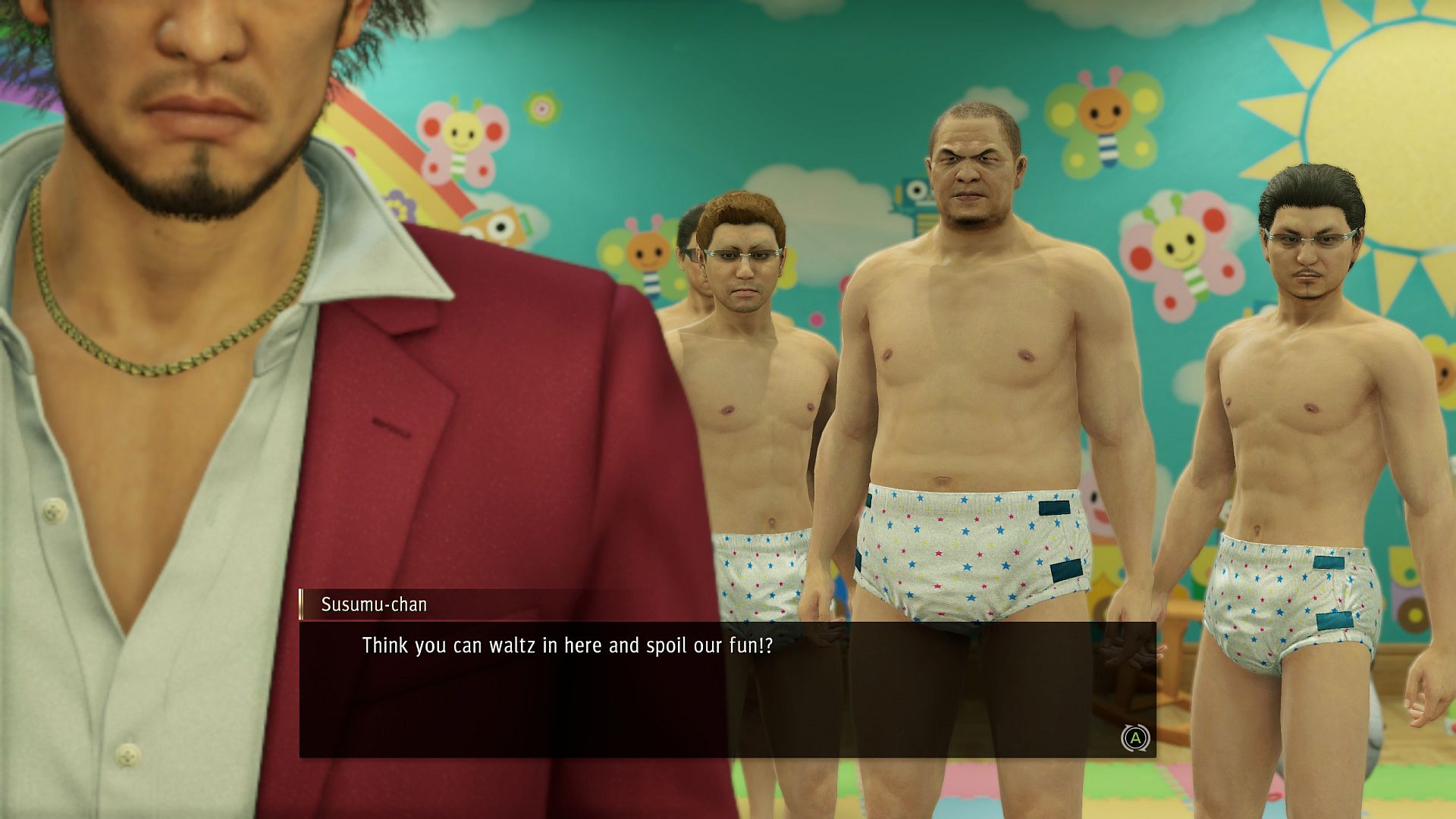

What really makes someone a hero? That’s the question at the heart of Yakuza: Like a Dragon, a game in which you’ll fight men slathered in lube, ride go-karts through the city streets, and ultimately battle to protect the legal ‘gray zone’ that serves as a home for society’s cast-offs.

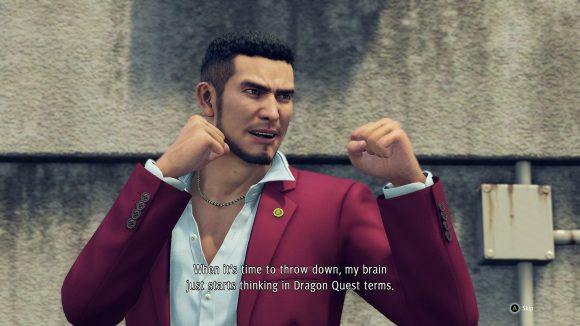

The latest in the long-running Yakuza series, Like a Dragon trades in the usual beat ’em up battle system for the turn-based battles of Dragon Quest, and while the transition isn’t entirely smooth, the result is one of the most charming and heartwarming games I’ve played in years.

Following his release from prison after serving 18 years in place of one of his small yakuza clan’s lieutenants, new protagonist Ichiban Kasuga finds himself in 2019 Yokohama as a man out of time. His attempts to reconnect with his former yakuza family result in him being shot and left for dead in a pile of garbage next to a homeless camp in the city of Isezaki Ijincho, with nothing but a blood-stained counterfeit bill and a disastrous Dragon Quest-style hairdo to his name.

Kasuga finds a friend in Nanba, a homeless former nurse who stitched his wounds and kept him alive, and Adachi, a disgraced police detective with a long-standing grudge against his old chief, and together the trio sets off into Ijincho to ‘level up’ by getting jobs and figuring out how to put their lives back together.

And so, off you go, penniless but rich in scruffy friends, into the similarly scruffy world of Ijincho’s nightlife district. Yakuza: Like a Dragon takes its time getting underway, but once it does you’ll find yourself swept up in its tale of rival gangs, the legal ‘gray zone’ they protect, and the strange and often broken people scraping by within it with nowhere else to turn.

Fans of the series can relax: the JRPG-style turn-based battle system manages its job or replacing Yakuza’s traditional beat ’em up brawling just fine, even if it lacks much in the way of meaningful depth or variation in practice. What’s far more interesting is how it manages to map Dragon Quest’s other elements over a dingy modern setting: your characters can change jobs at the local temp agency, and new gear can be found in local second-hand stores and sex shops. Quests come from convenience store clerks and washed-up actors, and you level up by studying or showing passion.

The pretext for shifting to a JRPG framework is found in Kasuga’s own biography: after spending almost the entirety of his adult life in prison, his only guiding light for how to succeed is his memory of the Dragon Quest games he played as a kid. Once he’s made his decision to become the hero, everything in his life is recontextualised as a role-playing game. Thanks largely to the sheer amount of different things Yakuza games tend to give you to do, this actually works, and Yakuza: Like a Dragon winds up being a JRPG that even JRPG-haters such as myself can enjoy.

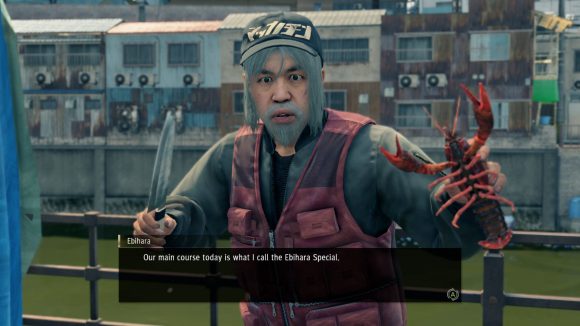

There really is a lot to do in Like a Dragon’s seedy Ijincho streets. Once it finally hits its cruising altitude, the story pulls you along in a twisting tale of murder and betrayal set against an uneasy truce between rival Japanese, Chinese, and Korean gangs. As in other Yakuza games, though, much of the joy is found in the constant distractions of mini-games and side stories, and the JRPG riffing in Like a Dragon provides even more of this stuff than ever before. A Yakuza version of Pokémon’s Professor Oak sends you off to fill in a ‘Sujidex’ with every species of weirdo haunting Ijincho’s alleys, there’s a certification school where you can take multiple-choice tests to improve your skills, and there’s even an endless procedurally generated dungeon to explore and grind for gear beneath the city’s streets. Between Dragon Kart racing, karaoke, and the surprisingly robust business management simulation that unlocks after several chapters, you’ll have plenty to keep you busy between narrative chunks.

Taken on their own, stripped of the context the Yakuza wrapper provides, none of these individual activities or game elements are particularly special. There are better kart racing games, deeper turn-based RPG combat systems, bigger open-world games to explore. But one of the defining characteristics of the Yakuza series is that these games are much more than the sum of their component parts, and Like a Dragon maintains this tradition magnificently. And since almost all of this side content is entirely optional, it’s rare that any of it gets in your way. It’s hard to be too disappointed in a so-so kart racing minigame when there’s darts to play and a city to save waiting just around the corner.

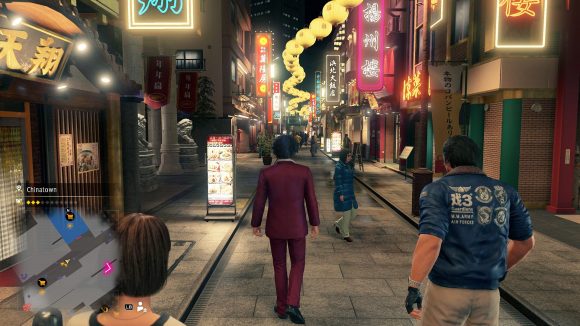

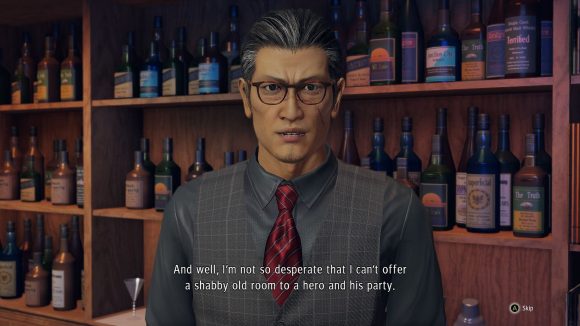

Roughly modeled on the real-life Yokohama district of Isezakicho, Yakuza: Like a Dragon’s Ijincho is split by a railway line that divides its swish business blocks from its seamier red light district, with a river walk area to the west (where Kasuga and his friends have a hideout in a local bar) and Chinatown to the east. It’s not a huge map, but there’s easily as much packed into its streets and alleys as you’ll find in the main series’ Kamurocho.

Read more: Check out the best action-adventure games on PC

From its cheap beef bowl joints and freelance thugs to its showy Chinatown storefronts, Like a Dragon’s Ijincho feels bustling with life, largely thanks to the game’s willingness to linger in grotesquely mundane scenes that feel much truer to day-to-day life than videogames generally are willing to get. You can stand by the river at night and watch the lights on the massive Ferris wheel in the distance before turning to look across at the tarps set up by the city’s homeless fishermen on the opposite bank. Like a Dragon is interested in people in all walks of life, and that interest in humanity is reflected in how it recontextualises Dragon Quest’s fantasy RPG mechanics and its own hard-boiled crime drama storyline.

With his head full of quixotic fantasies about dragons and heroes, even the unflappable Kasaga has to be physically shaken at one point to understand what Like a Dragon is trying to say. On his first day in the homeless camp where he awakens, he’s appalled by the conditions of the men living there. Sounding for all the world like an idealistic but uninformed bourgeois liberal, Kasuga suggests the problems can be solved if everyone heads with him to Hello Work, the temp agency nearby. But his new friend Nanba rebukes him.

“You don’t know what the hell you’re talking about,” Nanba shouts, squaring up to Kasuga amid the tragic squalor of the homeless camp. “Nobody lives like this by choice. This isn’t somewhere you choose to be, it’s somewhere you end up … And as much as some of us would love to go back, we can’t! And you think you can fix all that with just a quick trip to Hello Work?”

Nanba drives the point home: “You think we’re just too lazy to work? We all want a job and a living, man. But we can’t just erase all the things that keep us from having them! You can’t force people to be just like you. So knock it off.”

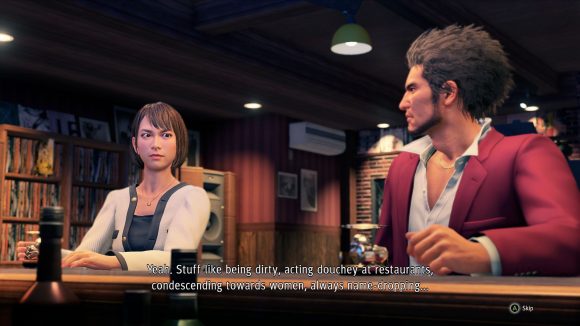

Fans of the Yakuza series tend to get a bit evangelical about them, and it’s not hard to see why: they’re games that try in earnest to understand human beings, and they want to see the best in everyone. Like a Dragon is no different on this front, whether it’s in giving its antagonists believable and understandable motivations or in nudging players to spend time talking with and learning about the friends they’ve picked up along their journey. There’s always time to lend an ear to your party members, but you have to choose to do it; Kasuga may be broke, but what he has plenty of is time to spend on his companions. One friend, bartender Saeko Mokouda, is worried about her twin sister, while Adachi frets about money.

The power of kindness has been a long-running thread in the Yakuza series, and in Like a Dragon, it’s shown to be the hero’s true source of power. Forging links with your party members makes you all better in battle, but digging into your friends’ backstories is genuinely rewarding in itself. Kindness is also the cord that binds all of Like a Dragon’s mismatched parts together, and it’s clear from each line of writing that it’s fundamental to the game. The villains are bad not because they’re gang members or rich prudes, but only when they lack empathy, kindness, and generosity. When sex workers appear in the frequent zany sub stories, it never feels exploitive or cruel – instead, the joke usually winds up helping Kasuga (and players, hopefully) understand their lives and aspirations better, and to recognise a shared humanity.

This wouldn’t have been possible for me to appreciate had it not been for the stellar work put into the English localisation by Sega of America. The Westernised version of Ryu Ga Gotoku’s script is full of heart and humour, and the English voiceover performances (should you choose dubs) are top-notch – at least when the script doesn’t steer things into outright camp, although that tends to be enjoyable for its own reasons anyway.

Related: The best RPG games on PC

Yakuza: Like a Dragon is not a perfect game and makes no real attempt to be. Its dungeons tend to be on the dull side and the new combat system, while serviceable, quickly becomes repetitive – and that’s a bit of a problem in a game that’s going to take you, at the extreme low end, 30 hours to finish. A few mini-games feel more perfunctory than fun, and it takes far too long to get any meaningful pushback from enemies. The crime drama storyline is compelling, but in the way that a pulpy action drama is compelling during a lazy Saturday afternoon Netflix binge.

Taken as a whole, though, Yakuza: Like a Dragon is one of this year’s must-play games. It can in turns be corny, weird, and melodramatic, sure. But its messiness is the recognisable, genre-defying messiness of human life, in which the funniest things will often happen to us when we’re angry or sad. It’s a life-affirming, heartwarming experience that I’ll be thinking back on with fondness for a very long time.